“Betty Pettersson didn't make it easy for herself, she constantly chose a different path from other women of her period and bumped up against several glass ceilings,” says Johanna Ringarp, lecturer at the Department of Education.

“In the 1870s, the normal route for women who wanted to work in education was to study at a teachers' college and then work in a girls' school. But Betty Pettersson first chose to study at a private school and then, as the first woman in Sweden, received an upper-secondary school diploma as soon as it became possible for women.”

Royal dispensation

After receiving her upper-secondary school diploma in 1871, she wanted to study humanities and languages at a university, but at that time women were not allowed to do so. Women were allowed to study medicine at universities as of 1870, but the humanities were considered masculine and were forbidden.

Betty Pettersson therefore had to write to the king and argue for an exemption. She succeeded and enrolled at Uppsala University in 1872. At that time, Betty Pettersson was the only female student amidst 1,544 male students at Uppsala University.

In 1875, Betty Pettersson graduated from the University, the first woman in Sweden to do so. A few years after Betty Pettersson enrolled at Uppsala University, women were given the right to graduate from the Faculty of Humanities and lower levels of the Faculty of Law.

Royal permission

After graduating, Betty Pettersson chose to bust one more glass ceiling by obtaining permission from the king to work as a teacher at a school for boys.

“Betty Pettersson broke new ground for the women who came after her. She showed that it was possible for women to study at university and work as teachers in boys' schools.”

Do we know anything about Betty Pettersson as a person?

“No, unfortunately there is not much evidence preserved. What is available are mostly parish registers and other archives where you can follow the general drift. But according to texts written after her death, she was considered a capable and well-liked educator.

“She must have possessed fierce motivation and plenty of opportunities in order to study at a private school,” Johanna Ringarp considers. “It can't have been easy to be the first one to strike the glass ceiling over and over again.”

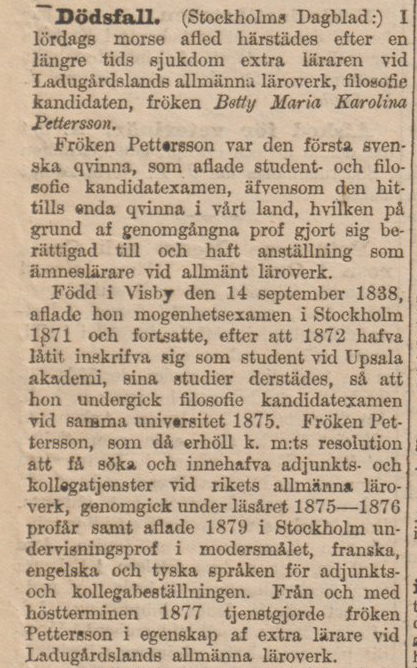

One piece of evidence that has been preserved and which Johanna Ringarp has sought out is an epitaph published in Svenska Dagbladet on Monday 9 February 1885.